What Building Automation's History Teaches Us About Building AI

What's possible with building AI? We can learn a lot by understanding where (and why) automation has struggled in the past.

In the Beginning...

When you look back, we have OPEC’s oil embargo to thank for kicking building automation into gear. The energy crunch of the mid-70s had everyone looking to automate tasks and operate leaner.

The first automation efforts were called the Energy 6-Pack (consisting of demand limiting, load rolling, optimal start & stop, and supply air and chilled and condenser water reset programming). But their results weren't enough.

The next step was to attach every sensor, actuator, and device through a panel as individual inputs to a minicomputer for monitoring and supervisory control. Thus was born the first BMS!

As long as these early systems were validated regularly, they worked well. But they were hard to update and needed constant attention to respond to changing conditions, which was more than most building teams had bandwidth for. Thus, also, was born our industry’s ongoing challenge of installation and commissioning.

Still, having a BMS at all was a leap forward in terms of the quality, timeliness, and scalability of building monitoring over watch tours, where operations staff manually logged gauge, meter, and temps every hour (and built bookcase after bookcase to house the binders of log sheets, where the data often sat unfindable and unused).

In the 80s, the U.S. finally began to let go of pneumatics and adopt electronic controls. Without the need to custom-design every building system and then pull miles of wire and custom-fit it all together, costs plummeted. But connections between direct digital controllers were crude. Communication between points was almost impossible, and manual adjustments were still more effective.

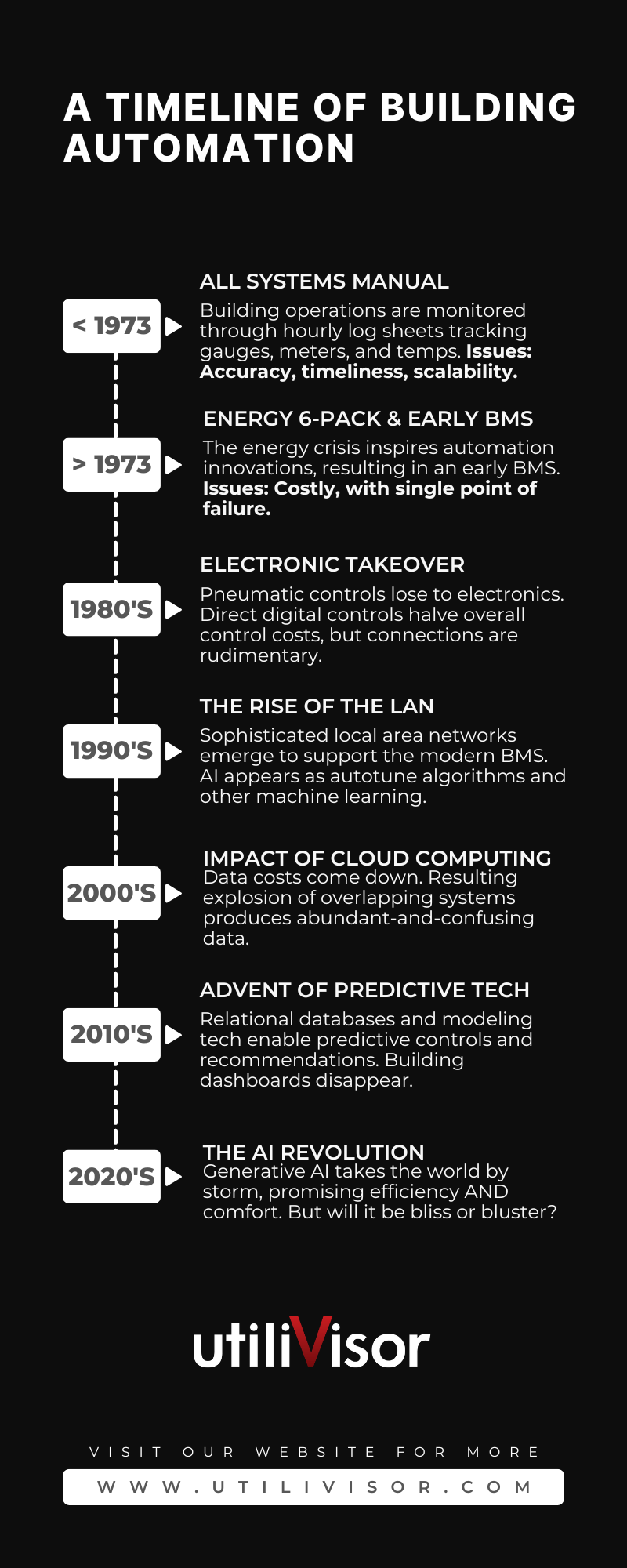

A Short History of Building Automation (by Decade)

The Advance(s) of Electronics

The switch to electronics also brought the ability to network. Now devices could send their data on local area networks (LANs), which were daisy-chained together to get the data to the BMS, which would review it and send instructions back out.

The next attempt at automation was to add a layer of algorithms, called an auto-tuner. These were either embedded into the BMS or as a black box solution on top of it, depending on the site. The goal of the auto-tuner was to make controls work “better.” The idea was sound enough: tuning algorithms are technically a viable solution. Unfortunately, they were unrealistic in practice. To begin with, too few operations teams knew how to validate these algorithms, so they were rarely set up correctly. Also, the algorithm also didn’t adapt fast enough to changing conditions. So instead of keeping pace with changes, their lag created an additional layer of problems and reduced control for operations staff. In the end, few properties kept up their auto-tuners, and they faded into the sunset with the Sony Walkman and the floppy disk.

In the ‘90s, the development of sophisticated computer architecture resulted in two major changes: 1) eliminating the building’s dependency on the BMS to monitor and supervise controls, and 2) lowering upfront and ongoing labor costs of the BMS.

But it wasn’t all puppies and roses. All these early computer systems were proprietary, which meant high costs and little customer sway. You couldn’t even buy a thermostat off the shelf and use it: you could only use the specific (and expensive!) part from your supplier. The arrival of BACnet and the subsequent standardization in communication protocols and parts eventually transformed what had been a very customized environment into something far more open and interchangeable.

Suddenly, building automation could be easier and less expensive than ever before. But it didn’t achieve that much more.

The problem was that the cost of data storage was still high. Although the automation systems at this time were capable of producing fountains of building energy data, they had to store the data on-site, which jacked up the cost of the system. So instead, these systems produced only a trickle of operational data because the vendors wanted to keep the cost of purchasing their systems low. The result was that the cost of troubleshooting problems down the line stayed high and didn’t create any value for the building operators, who went back to operating the systems manually.

The Cloud's Silver Lining

The advent of cloud computing brought a drop in the costs as well as the difficulty of analyzing large data sets like building energy usage. This development exposed a level of detail we couldn’t know before, making it much easier to visualize causes and effects. On the negative side, it also inherently produces a firehose of inaccurate data consisting of a little signal and lots of noise.

Happily, software engineers embraced this Big Data challenge quickly, using relational databases and developing new modeling techniques to sift through the data and pull out what’s meaningful. At the same time, we lose “in building” dashboards. Today, through careful human training and validation, large data models can be taught to recognize patterns, which enable predictive controls and recommendations that have vastly improved the capabilities of building automation.

Today, we are entering the generative AI phase, where statistical models are trained to make predictions from training data about a dynamic situation without supervision. This is a significant departure from previous practices.

We need to remember what generative AI is – a statistical model based on probabilities found in the training data. Therefore, its results are directly impacted by the quality and appropriateness of the data and its suitability for the chosen building. Will the training data be continuously updated to accurately reflect the target assets? That would be a first.

The advent of AI has also allowed the “auto-tuners” from the past to rebrand themselves. Now they remotely analyze and then push new algorithms back into the BMS, which is dangerous in central utility plants and large office buildings and further distances building operators from their buildings.

Automation Is a Journey, Not a Destination

Can AI be taught to keep buildings truly safe, comfortable, and efficient?

The task it’s being given is very complex. In short, the AI should be able to:

1) maintain occupant comfort while

2) increasing energy savings

3) over multiple dynamic conditions and while

4) communicating effectively with the grid

5) in real time.

That’s a lot to manage for any form of intelligence, especially one in its infancy.

Right now, AI is all promise, unknowns, and euphoric sales hype. We still can't answer basic questions, such as initial purchase price, cost of installation and training, cost of ongoing maintenance and refinement, obsolescence and removal/replacement costs, timeliness of deliverability, and scalability. What we can be sure of is that generative AI – like every other advancement in building tech – will have to reckon with our industry’s perpetual challenges of accuracy, availability, repeatability, and timeliness.

In short, the future of building operations will most certainly continue to include AI. But don’t expect it to eliminate the main challenges in building operations. Those are timeless. Anyone who tells you differently is selling a fantasy.

Despite the shine of technology, a real and lasting solution is still one that prioritizes experience and control at the plant. A partnership between a third-party monitoring company that specializes in building operations and the onsite operations team is and will continue to be the most cost-effective solution to operational challenges.

This article was 100% written by a human. Building images were generated using Midjourney.

Interested in more on AI in building operations?

Read "AI: Hero or Hype?"About utiliVisor

Your tenant submetering and energy plant optimization services are an essential part of your operation. You deserve personalized energy insights from a team that knows buildings from the inside out, applies IoT technology and is energized by providing you with accurate data and energy optimization insights. When you need experience, expertise, and service, you need utiliVisor on your side, delivering consistent energy and cost-saving strategies to you. What more can our 45+ years of experience and historical data do for you? Call utiliVisor at 212-260-4800 or visit utilivisor.com